- Home

- Ronald Firbank

Sorrow in Sunlight

Sorrow in Sunlight Read online

Ronald Firbank

Sorrow in Sunlight

(1925)

[Alternatively entitled ‘Prancing Nigger’]

Table of Contents

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

I

Looking gloriously bored, Miss Miami Mouth gaped up into the boughs of a giant silk-cotton tree. In the lethargic noontide nothing stirred: all was so still, indeed, that the sound of someone snoring was clearly audible among the cane-fields far away.

“After dose yams an’ pods an’ de white falernum, I dats way sleepy too,” she murmured, fixing heavy somnolent eyes upon the prospect that lay before her.

Through the sun-tinged greenery shone the sea, like a floor of silver glass strewn with white sails.

Somewhere out there, fishing, must be her boy, Bamboo!

And, inconsequently, her thoughts wandered from the numerous shark-casualties of late to the mundane proclivities of her mother; for to quit the little village of Mediavilla for the capital was that dame’s fixed obsession.

Leave Mediavilla, leave Bamboo! The young negress fetched a sigh.

In what, she reflected, way would the family gain by entering society, and how did one enter it, at all? There would be a gathering, doubtless, of the elect (probably armed), since the best society is exclusive, and difficult to enter. And then? Did one burrow? Or charge? She had sometimes heard it said that people “pushed”… and closing her eyes, Miss Miami Mouth sought to picture her parents, assisted by her small sister, Edna, and her brother, Charlie, forcing their way, perspiring, but triumphant, into the highest social circles of the city of Cuna-Cuna.

Across the dark savannah country the city lay, one of the chief alluring cities of the world: The Celestial city of Cuna-Cuna, Cuna, city of Mimosa, Cuna, city of Arches, Queen of the Tropics, Paradise—almost invariably travellers referred to it like that.

Oh, everything must be fantastic there, where even the very pickneys put on clothes! And Miss Miami Mouth glanced fondly down at her own plump little person, nude, but for a girdle of creepers that she would gather freshly twice a day.

“It would be a shame, sh’o, to cover it,” she murmured drowsily, caressing her body, and moved to a sudden spasm of laughter, she tittered: “No! really. De ideah!”

II

“Silver bean-stalks, silver bean-stalks, oh hé, oh hé,” down the long village street, from door to door, the cry repeatedly came, until the vendor’s voice was lost on the evening air.

In a rocking chair, before the threshold of a palm thatched cabin, a matron with broad, bland features, and a big, untidy figure, surveyed the scene with a nonchalant eye.

Beneath some tall trees, bearing flowers like flaming bells, a few staid villagers sat enjoying the rosy dusk, while, strolling towards the sea, two young men passed by with fingers intermingled.

With a slight shrug, the lady plied her fan.

As the Mother of a pair of oncoming girls, the number of ineligible young men, or confirmed bachelors around the neighbourhood was a constant source of irritation to her.

“Sh’o, dis remoteness bore an’ weary me to death,” she exclaimed, addressing someone through the window behind; and receiving no audible answer, she presently rose, and went within.

It was the hour when, fortified by a siesta, Mrs. Ahmadou Mouth was wont to approach her husband on general household affairs, and to discuss, in particular, the question of their removal to the town; for, with the celebration of their Pearl-wedding, close at hand, the opportunity to make the announcement of a change of residence to their guests, ought not, she believed, to be missed.

“We leave Mediavilla for de education ob my daughters,” she would say; or, perhaps: “We go to Cuna-Cuna, for de finishing ob mes filles!”

But, unfortunately, the reluctance of Mr. Mouth to forsake his Home seemed to increase from day to day.

She found him asleep, bolt upright, his head gently nodding, beneath a straw-hat beautifully browned.

“Say, nigger, lub,” she murmured, brushing her hand featheringly along his knee, “say, nigger, lub, I gotta go!”

It was the tender prelude to the storm.

Evasive (and but half-awake), he warned her. “Let me alone; Ah’m thinkin’.”

“Prancing Nigger, now come on!”

“Ah’m thinkin’.”

“Tell me what for dis procrastination?” Exasperated, she gripped his arm.

But for all reply, Mr. Mouth drew a volume of revival hymns towards him, and turned on his wife his back.

“You ought to sae o’ you-self, sh’o,” sh caustically commented, crossing to the window.

The wafted odours of the cotton trees without oppressed the air. In the deepening twilight, the rising moonmist, already obscured the street.

“Dis placee not healthy. Dat damp! Should my daughters go off into a decline…” she apprehensively murmured, as her husband started softly to sing.

“For ebber wid de Lord!

Amen; so let it be

Life from de dead is in dat word

’Tis immortality.”

“If it’s de meting-house dats de obstruction, dair are odders, too, in Cuna-Cuna,” she observed.

“How often hab I bid you nebba to mention dat modern Sodom in de hearing ob my presence!”

“De Debil frequent de village, fo’ dat matter, besides de town.”

“Sh’o nuff.”

“But yestiddy, dat po’ silly negress Ottalie was seduced again in a Mango track—; an’ dats de third time!”

“Heah in de body pent,

Absent from Him I roam

Yet nightly pitch my movin’ tent

A day’s march nearer home.”

“Prancing Nigger, from dis indifference to your fambly, be careful lest you do arouse the vials ob de Lord’s wrath!”

“Yet nightly pitch—” he was beginning again, in a more subdued key, but the tones of his wife arrested him.

“Prancing Nigger, lemme say sumptin’ more!” Mrs. Mouth took a long sighing breath: “In dis dark jungle my lil jewel Edna, I feah, will wilt away…”

“Wh’a gib you cause to speak like dat?”

“I was tellin’ my fortune lately wid de cards,” she reticently made reply, insinuating, by her half-turned eyes, that more disclosures of an ominous nature concerning others besides her daughter had been revealed to her as well.

“Lordey Lord; what is it den you want?”

“I want a Villa with a watercloset—” flinging wiles to the winds, it was a cry from the heart.

“De Lord hab pity on dese vanities an’ innovations!”

“In town, you must rememba, often de houses are far away from de parks;—de city, in dat respect, not like heah.”

“Say nothin’ more! De widow ob my po’ brudder Willie, across de glen, she warn me I ought nebba to listen to you.”

“Who care for a common woman, dat only read de ‘Negro World,’ an’ nebba see anyt’ing else!” she swelled.

Mr. Mouth turned conciliatingly.

“To-morrow me arrange for de victuals for our ebenin’ at Home!”

“Good, bery fine,” she murmured, acknowledging through the window the cordial “good-night” of a few late labourers, returning from the fields, each with a bundle of sugar-cane poised upon the head.

“As soon as marnin’ dawn me take dis bizniz in hand.”

“Only pramas, nigger darlin’,” she cajoled, “dat durin’ de course ob de reception, you make a lil speech to inform de

neighbours ob our gwine away bery soon, for de sake of de education ob our girls.”

“Ah sh’an’ pramas nothing’.”

“I could do wid a change too, honey, after my last miscarriage.”

“Change come wid our dissolution,” he assured her, “quite soon enuff!”

“Bah,” she murmured, rubbing her cheek to his: “we set out on our journey sh’o in de season ob Novemba.”

To which with asperity he replied: “Not for two Revolutions!” and rising brusquely, strode solemnly from the room.

“Hey-ho-day,” she yawned, starting a wheezy gramophone, and sinking down upon his empty chair; and she was lost in ball-room fancies (whirling in the arms of some blonde young foreigner) when she caught sight of her daughter’s reflection in the glass.

Having broken, or discarded her girdle of leaves, Miss Miami Mouth, attracted by the gramophone, appeared to be teaching a hectic two-step to the cat.

“Fie, fie, my lass. Why you be so Indian?” her mother exclaimed, bestowing with the full force of a carpet-slipper, a well-aimed spank from behind.

“Aïe, aïe!”

“Sh’o: you nohow select!”

“Aïe…”

“De low exhibition!”

“I had to take off my apron, ’cos it seemed to draw de bees,” Miami tearfully explained, catching up the cat in her arms.

“Ob course, if you choose to wear roses…”

“It was but ivy!”

“De berries ob de ivy entice de same,” Mrs. Mouth replied, nodding graciously, from the window, to Papy Paul, the next door neighbour, who appeared to be taking a lonely stroll with a lanthorn and a pineapple.

“I dats way wondering why Bamboo, no pass, dis ebenin’, too; as a rule, it is seldom he stop so late out upon de sea,” the young girl ventured.

“After I shall introduce you to de world (de advantage ob a good marriage; when I t’ink ob mine!), you will be ashamed, sh’o, to recall this infatuation.”

“De young men ob Cuna-Cuna (tell me, Mammee), are dey den so nice?”

“Ah, Chile! If I was your age again…”

“Sh’o, dair’s nothin’ so much in dat.”

“As a young girl of eight (Tee-hee!) I was distracting to all the gentlemen,” Mrs. Mouth asserted, confiding a smile to a small, long-billed bird, in a cage, of the variety known as Bequia-Sweet.

“How I wish I’d been born, like you, in August-Town, across de Isthmus!”

“It gib me dis taste fo’ S’ciety, Chile.”

In S’ciety, don’t dey dress wid clothes on ebery day?”

“Sh’o; surtainly.”

“An’ don’t dey nebba tickle?”

“In August-Town, de aristocracy conceal de best part ob deir bodies; not like heah!”

“An’ tell me, Mamme…? De first lover you eber had… was he half as handsome as Bamboo?”

“De first dude, Chile, I eber had, was a lil, lil buoy,…wid no hair (whatsoeber at all,) bal’ like a calabash!” Mrs. Mouth replied, as her daughter Edna entered with the lamp.

“Frtt!” the wild thing tittered, setting it down with a bang: with her cincture of leaves and flowers, she had the éclat of a butterfly.

“Better fetch de shade,” Mrs. Mouth exclaimed, staring squeamishly at Miami’s shadow on the wall.

“Already it grow dark; no one about now at dis hour ob night at all.”

“Except thieves an’ ghouls,” Mrs. Mouth replied, her glance straying towards the window.

But only the little blue winged bats were passing beneath a fairyland of stars.

“When I do dis, or dis, my shadow appear as formed as Mimi’s!”

“Sh’o, Edna, she dat provocative to-day.”

“Be off at once Chile, an’ lay de table for de ebenin’ meal; an’ be careful not to knock de shine off de new tin teacups,” Mrs. Mouth commanded, taking up an Estate-Agent’s catalogue and seating herself comfortably beneath the lamp.

“‘City of Cuna-Cuna,’” she read, “‘in the Heart of a Brainy District, (within easy reach of University, shops, etc.) A charming, Freehold Villa. Main drainage. Extensive views. Electric light. Every convenience.’”

“Dat sound just de sort ob lil shack for me.”

III

The strange sadness of evening, the détresse of the Evening Sky! Cry, cry white Rain Birds out of the West, cry…!

“An’ so, Miami, you no come back no more?”

“No, no come back.”

Flaunting her boredom by the edge of the sea one close of day, she had chanced to fall in with Bamboo, who, stretched at length upon the beach, was engaged in mending a broken net.

“An’ I dats way glad,” she half-resentfully pouted, jealous a little of his toil.

But, presuming deafness, the young man laboured on, since, to support an aged mother, and to attain one’s desires, perforce necessitates work; and his fondest wish, by dint of saving, was to wear on his wedding-day a pink starched cotton shirt—a starched, pink cotton shirt, stiff as a boat’s-sail when the North winds caught it! But a pink shirt would mean trousers… and trousers would lead to shoes… “Extravagant nigger, don’t you dare!” he would exclaim, in dizzy panic, from time to time, aloud.

“Forgib me, honey,” he begged, “but me obliged to finish while de daylight last.”

“Sh’o,” she sulked, following the amazing strategy of the sunset-clouds.

“Miami angel, you look so sweet: I dat amorous ob you, Mimi!”

A light laugh tripped over her lips:

“Say buoy, how you getting on?” she queried, sinking down on her knees beside him.

“I dat amorous ob you!”

“Oh, ki,” she tittered, with a swift mocking glance at his crimson loincloth. She had often longed to snatch it away.

“Say you lub me, just a lil, too, deah?”

“Sh’o,” she answered softly, sliding over on to her stomach, and laying her cheek to the flats of her hands.

Boats with crimson spouts, to wit, steamers, dotted the skyline far away, and barques, with sails like the wings of butterflies, borne by an idle breeze, were bringing more than one ineligible young mariner, back to the prose of shore.

“Ob wha’ you t’inking?”

“Nothin’,” she sighed, contemplating laconically a little transparent shell of violet pearl, full of sea-water and grains of sand, that the wind ruffled as it blew.

“Not ob any sort ob lil t’ing?” he caressingly insisted, breaking an open dark flower from her belt of wild Pansy.

“I should be gwine home,” she breathed, recollecting the undoing of the negress Ottalie.

“Oh, I dat amorous ob you, Mimi.”

“If you want to finish dat net while de daylight last.”

For oceanward, in a glowing ball, the sun had dropped already.

“Sho’, nigger, I only wish to be kind,” she murmured, getting up and sauntering a few paces along the strand.

Lured, perhaps, by the nocturnal phosphorescence from its lair, a water-scorpion, disquited at her approach, turned and vanished amid the sheltering cover of the rocks. “Isht, isht,” she squaled, wading after it into the surf; but to find it, look as she would, was impossible. Dark, curious and anxious, in the fast failing light, the sea disquited her too, and it was consoling to hear close behind her the solicitous voice of Bamboo.

“Us had best soon be movin’, befo’ de murk ob night.”

The few thatched cabins that comprised the village of Mediavilla lay not half a mile from the shore. Situated between the savannah and the sea, on the southern side of the island known as Tacarigua (the “burning Tacarigua” of the Poets), its inhabitants were obliged, from lack of communication with the large island centres, to rely to a considerable extent for a livelihood among themselves. Local Market days, held, alternatively, at Valley Village or Broken Hill (the nearest approach to industrial towns in the district around Mediavilla), were the chief source of rural trade, when such merchandise as fish, co

ral, beads, bananas and loincloths would exchange hands amid much animation, social gossip and pleasant fun.

“Wha’ you say to dis?” she queried as they turned inland through the cane-fields, holding up a fetish known as a “luck-ball,” attached to her throat by a chain.

“Who gib it you?” he shortly demanded, with a quick suspicious glance.

“Mammee, she bring it from Valley Village, an’ she bring another for my lil sister, too.”

“Folks say she attend de Market only to meet the Obi man, who cast a spell so dat your Dada move to Cuna-Cuna.”

“Dat so!”

“Your Mammee no seek ebber de influence ob Obeah?”

“Not dat I know ob!” she replied; nevertheless, she could not but recall her mother’s peculiar behaviour of late, especially upon Market days, when, instead of conversing with her friends, she would take herself off with a mysterious air, saying she was going to the Baptist Chapel.

“Mammee, she hab no faith in de Witch-Doctor at all,” she murmured, halting to lend an ear to the liquid note of a peadove among the canes.

“I no care; me follow after wherebber you go,” he said, stealing an arm about her.

“True?” she breathed, looking up languidly towards the white mounting moon.

“I dat amorous ob you, Mimi.”

IV

It was the Feast night. In the grey spleen of evening, through the dusty lanes towards Mediavilla county society flocked.

Peering round a cow-shed door, Primrose and Phoebe, procured as waitresses for the occasion, felt their valour ooze as they surveyed the arriving guests, and dropping prostrate amid the straw, declared, in each other’s arms, that never, never would they find the courage to appear.

In the road, before a tall tamarind-tree, a well-spread supper board exhaled a pungent odour of fried cascadura fish, exciting the plaintive ravings of the wan pariah dogs, and the cries of a few little stark naked children engaged as guardians to keep them away. Defying an ancient and inelegant custom by which the hosts welcomed their guests by the side of the road, Mrs. Mouth had elected to remain within the precincts of the house, where, according to tradition, the bridal trophies—cowrie-shells, feathers, and a bouquet of faded orange blossom—were being displayed.

The Flower Beneath the Foot

The Flower Beneath the Foot Sorrow in Sunlight

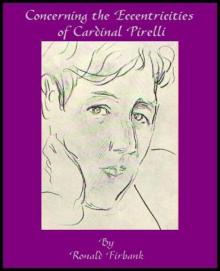

Sorrow in Sunlight Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli

Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli