- Home

- Ronald Firbank

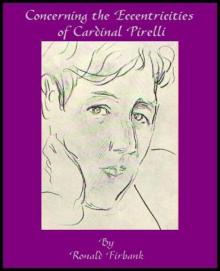

Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli

Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli Read online

CONCERNING THE ECCENTRICITIES OF CARDINAL PIRELLI

By RONALD FIRBANK

First published in England 1926; New Edition 1929

I

Huddled up in a cope of gold wrought silk he peered around. Society had rallied in force. A christening—and not a child's.

Rarely had he witnessed, before the font, so many brilliant people. Were it an heir to the DunEden acres (instead of what it was) the ceremony could have hardly drawn together a more distinguished throng.

Monsignor Silex moved a finger from forehead to chin, and from ear to ear. The Duquesa DunEden's escapades, if continued, would certainly cost the Cardinal his hat.

"And ease my heart by splashing fountains."

From the choir-loft a boy's young voice was evoking Heaven.

"His hat!" Monsignor Silex exclaimed aloud, blinking a little at the immemorial font of black Macæl marble that had provoked the screams of pale numberless babies.

Here Saints and Kings had been baptized, and royal Infantas, and sweet Poets, whose high names thrilled the heart.

Monsignor Silex crossed his breast. He must gather force to look about him. Frame a close report. The Pontiff, in far-off Italy, would expect precision.

Beneath the state baldequin, or Grand Xaymaca, his Eminence sat enthroned ogled by the wives of a dozen grandees. The Altamissals, the Villarasas (their grandee-ships' approving glances, indeed, almost eclipsed their wives'), and Catherine, Countess of Constantine, the most talked-of beauty in the realm, looking like some wild limb of Astaroth in a little crushed "toreador" hat round as an athlete's coif with hanging silken balls, while beside her a stout, dumpish dame, of enormous persuasion, was joggling, solicitously, an object that was of the liveliest interest to all.

Head archly bent, her fine arms divined through darkling laces, the Duquesa stood, clasping closely a week-old police-dog in the ripple of her gown.

"Mother's pet!" she cooed, as the imperious creature passed his tongue across the splendid uncertainty of her chin.

Monsignor Silex's large, livid face grew grim.

What,—disquieting doubt,—if it were her Grace's offspring after all? Praise heaven, he was ignorant enough regarding the schemes of nature, but in an old lutrin once he had read of a young woman engendering a missel-thrush through the channel of her nose. It had created a good deal of scandal to be sure at the time: the Holy Inquisition, indeed, had condemned the impudent baggage, in consequence, to the stake.

"That was the style to treat them," he murmured, appraising the assembly with no kindly eye. The presence of Madame San Seymour surprised him; one habitually so set apart and devout! And Madame La Urench, too, gurgling away freely to the four-legged Father: "No, my naughty Blessing; no, not now!... By and by, a bone."

Words which brought the warm saliva to the expectant parent's mouth.

Tail awag, sex apparent (to the affected slight confusion of the Infanta Eulalia-Irene), he crouched, his eyes fixed wistfully upon the nozzle of his son.

Ah, happy delirium of first parenthood! Adoring pride! Since times primæval by what masonry does it knit together those that have succeeded in establishing here, on earth, the vital bonds of a family's claim? Even the modest sacristan, at attention by the font, felt himself to be superior of parts to a certain unproductive chieftain of a princely House, who had lately undergone a course of asses' milk in the surrounding mountains—all in vain!

But, supported by the Prior of the Cartuja, the Cardinal had arisen for the act of Immersion.

Of unusual elegance, and with the remains, moreover, of perfect looks, he was as wooed and run after by the ladies as any matador.

"And thus being cleansed and purified, I do call thee 'Crack'!" he addressed the Duquesa's captive burden.

Tail sheathed with legs "in master's drawers," ears cocked, tongue pendent....

"Mother's mascot!"

"Oh, take care, dear; he's removing all your rouge!"

"What?"

"He's spoilt, I fear, your roses." The Countess of Constantine tittered.

The Duquesa's grasp relaxed. To be seen by all the world at this disadvantage.

"Both?" she asked, distressed, disregarding the culprit, who sprang from her breast with a sharp, sportive bark.

What rapture, what freedom!

"Misericordia!" Monsignor Silex exclaimed, staring aghast at a leg poised, inconsequently, against the mural-tablet of the widowed duchess of Charona—a woman who, in her lifetime, had given over thirty million pezos to the poor!

Ave Maria purissima! What challenging snarls and measured mystery marked the elaborate recognition of father and son, and would no one then forbid their incestuous frolics?

In agitation Monsignor Silex sought fortitude from the storied windows overhead, aglow in the ambered light as some radiant missal.

It was Saint Eufraxia's Eve, she of Egypt, a frail unit numbered above among the train of the Eleven Thousand Virgins: an immaturish schoolgirl of a saint, unskilled, inexperienced in handling a prayer, lacking, the vim and native astuteness of the incomparable Theresa.

Yes; divine interference, 'twixt father and son, was hardly to be looked for, and Eufraxia (she of Egypt) had failed too often before....

Monsignor Silex started slightly, as, from the estrade beneath the dome, a choir-boy let fall a little white spit.

Dear child, as though that would part them!

"Things must be allowed to take their 'natural' course," he concluded, following the esoteric antics of the reunited pair.

Out into the open, over the Lapis Lazuli of the floor, they flashed, with stifled yelps, like things possessed.

"He'll tear my husband's drawers!" the duquesa lamented.

"The duque's legs. Poor Decima." The Infanta fell quietly to her knees.

"Fortify ... asses ..." the royal lips moved.

"Brave darling," she murmured, gently rising.

But the duquesa had withdrawn, it seemed, to repair her ravaged roses, and from the obscurity of an adjacent confessional-box was calling to order Crack.

"Come, Crack!"

And to the Mauro-Hispanic rafters the echo rose.

"Crack, Crack, Crack, Crack...."

II

From the Calle de la Pasiôn, beneath the blue-tiled mirador of the garden wall, came the soft brooding sound of a seguidilla. It was a twilight planned for wooing, unbending, consent; many, before now, had come to grief on an evening such. "It was the moon."

Pacing a cloistered walk, laden with the odour of sun-tired flowers, the Cardinal could not but feel the insidious influences astir. The bells of the institutions of the Encarnacion and the Immaculate Conception, joined in confirming Angelus, had put on tones half-bridal, enough to create vague longings, of sudden tears, among the young patrician boarders.

"Their parents' daughters—convent-bred," the Cardinal sighed.

At the Immaculate Conception, dubbed by the Queen, in irony, once "The school for harlots," the little Infanta Maria-Paz must be lusting for her Mamma and the Court, and the lilac carnage of the ring, while chafing also in the same loose captivity would be the roguish niñas of the pleasure-loving duchess of Sarmento, girls whose Hellenic ethics had given the good Abbess more than one attack of fullness.

Morality. Poise! For without temperance and equilibrium—— The Cardinal halted.

But in the shifting underlight about him the flushed camellias and the sweet night-jasmines suggested none; neither did the shape of a garden-Eros pointing radiantly the dusk.

"For unless we have balance——" the Cardinal murmured, distraught, admiring against the elusive nuances of

the afterglow the cupid's voluptuous hams.

It was against these, once, in a tempestuous mood that his mistress had smashed her fan-sticks.

"Would that all liaisons would break as easily!" his Eminence framed the prayer: and musing on the appalling constancy of a certain type, he sauntered leisurely on. Yes, enveloping women like Luna Sainz, with their lachrymose, tactless "mys," how shake them off? "My" Saviour, "my" lover, "my" parasol—and, even, "my" virtue....

"Poor dearie."

The Cardinal smiled.

Yet once in a way, perhaps, he was not averse to being favoured by a glimpse of her: "A little visit on a night like this." Don Alvaro Narciso Hernando Pirelli, Cardinal-Archbishop of Clemenza, smiled again.

In the gloom there, among the high thickets of bay and flowering myrtle.... For, after all, bless her, one could not well deny she possessed the chief essentials: "such, poor soul, as they are!" he reflected, turning about at the sound as of the neigh of a horse.

"Monseigneur...."

Bearing a biretta and a silver shawl, Madame Poco, the venerable Superintendent-of-the-palace, looking, in the blue moonlight, like some whiskered skull, emerged, after inconceivable peepings, from among the leafy limbo of the trees.

"Ah, Don Alvaro, sir! Come here."

"Pest!" His Eminence evinced a touch of asperity.

"Ah, Don, Don,..." and slamming forward with the grace of a Torero lassooing a bull, she slipped the scintillating fabric about the prelate's neck.

"Such nights breed fever, Don Alvaro, and there is mischief in the air."

"Mischief?"

"In certain quarters of the city you would take it almost for some sortilege."

"What next?"

"At the Encarnacion there's nothing, of late, but seediness. Sister Engracia with the chicken-pox, and Mother Claridad with the itch, while at the College of Noble Damosels, in the Calle Santa Fé, I hear a daughter of Don José Illescas, in a fit of caprice, has set a match to her coronet."

"A match to her what?"

"And how explain, Don Alvaro of my heart, these constant shots in the Cortès? Ah, sangre mio, in what times we live!"

Ambling a few steps pensively side by side, they moved through the brilliant moonlight. It was the hour when the awakening fireflies are first seen like atoms of rosy flame floating from flower to flower.

"Singular times, sure enough," the Cardinal answered, pausing to enjoy the transparent beauty of the white dripping water of a flowing fountain.

"And ease my heart by splashing—tum-tiddly-um-tum," he hummed. "I trust the choir-boys, Dame, are all in health?"

"Ah, Don Alvaro, no, sir!"

"Eh?"

"No, sir," Madame Poco murmured, taking up a thousand golden poses.

"Why, how's that?"

"But few now seem keen on Leapfrog, or Bossage, and when a boy shows no wish for a game of Leap, sir, or Bossage——"

"Exactly," his Eminence nodded.

"I'm told it's some time, young cubs, since they've played pranks on Tourists! Though only this afternoon little Ramón Ragatta came over queazy while demonstrating before foreigners the Dance of the Arc, which should teach him in future not to be so profane: and as to the acolytes, Don Alvaro, at least half of them are absent, confined to their cots, in the wards of the pistache Fathers!"

"To-morrow, all well, I'll take them some melons."

"Ah, Don, Don!!"

"And, perhaps, a cucumber," the Cardinal added, turning valedictionally away.

The tones of the seguidilla had deepened and from the remote recesses of the garden arose a bedlam of nightingales and frogs.

It was certainly incredible how he felt immured.

Yet to forsake the Palace for the Plaza he was obliged to stoop to creep.

With the Pirelli pride, with resourceful intimacy he communed with his heart: deception is a humiliation; but humiliation is a Virtue—a Cardinal, like myself, and one of the delicate violets of our Lady's crown.... Incontestably, too,—he had a flash of inconsequent insight, many a prod to a discourse, many a sapient thrust, delivered ex cathedrâ, amid the broken sobs of either sex, had been inspired, before now, by what prurient persons might term, perhaps, a "frolic." But away with all scruples! Once in the street in mufti, how foolish they became.

The dear street. The adorable Avenidas. The quickening stimulus of the crowd: truly it was exhilarating to mingle freely with the throng!

Disguised as a cabellero from the provinces or as a matron (disliking to forgo altogether the militant bravoura of a skirt), it became possible to combine philosophy, equally, with pleasure.

The promenade at the Trinidades seldom failed to be diverting, especially when the brown Bettita or the Ortiz danced! Olé, he swayed his shawl. The Argentina with Blanca Sanchez was amusing too; her ear-tickling little song "Madrid is on the Manzanares," trailing the "'ares" indefinitely, was sure, in due course, to reach the Cloisters.

Deliberating critically on the numerous actresses of his diocese, he traversed lightly a path all enclosed by pots of bergamot.

And how entrancing to perch on a bar-stool, over a glass of old golden sherry!

"Ah Jesus-Maria," he addressed the dancing lightning in the sky.

Purring to himself, and frequently pausing, he made his way, by ecstatic degrees, towards the mirador on the garden wall.

Although a mortification, it was imperative to bear in mind the consequences of cutting a too dashing figure. Beware display. Vanity once had proved all but fatal: "I remember it was the night I wore ringlets and was called 'my queen.'"

And with a fleeting smile, Don Alvaro Pirelli recalled the persistent officer who had had the effrontery to attempt to molest him: "Stalked me the whole length of the Avenue Isadora!" It had been a lesson. "Better to be on the drab side," he reflected, turning the key of the garden tower.

Dating from the period of the Reformation of the Nunneries, it commanded the privacy of many a drowsy patio.

"I see the Infanta has begun her Tuesdays!" he serenely noted, sweeping the panorama with a glance.

It was a delightful prospect.

Like some great guitar the city lay engirdled ethereally by the snowy Sierras.

"Foolish featherhead," he murmured, his glance falling upon a sunshade of sapphire chiffon, left by Luna: "'my' parasol!" he twirled the crystal hilt.

"Everything she forgets, bless her," he breathed, lifting his gaze towards the magnolia blossom cups that overtopped the tower, stained by the eternal treachery of the night to the azure of the Saint Virgin. Suspended in the miracle of the moonlight their elfin globes were at their zenith.

"Madrid is on the Manzan-ares," he intoned.

But "Clemenza," of course, is in white Andalucia.

III

After the tobacco-factory and the railway-station, quite the liveliest spot in all the city was the cathedral-sacristia. In the interim of an Office it would be besieged by the laity, often to the point of scrimmage: aristocrats and mendicants, relatives of acolytes—each had some truck or other in the long lofty room. Here the secretary of the chapter, a burly little man, a sound judge of women and bulls, might be consulted gratis, preferably before the supreme heat of day. Seated beneath a sombre study of the Magdalen waylaying our Lord (a work of wistful interest ascribed to Valdés Leal), he was, with tactful courtesy, at the disposal of anyone soliciting information as to "vacant dates," or "hours available," for some impromptu function. Indulgences, novenas, terms for special masses—with flowers and music? Or, just plain; the expense, it varied! Bookings for baptisms, it was certainly advisable to book well ahead; some mothers booked before the birth—; ah-hah, the little Juans and Juanas; the angelic babies! And arrangements for a corpse's lying-in-state: "Leave it to me." These, and such things, were in his province.

But the secretarial bureau was but merely a speck in the vast shuttered room. As a rule, it was by the old pagan sarcophaguses, outside the vestry-door, "waiting for Father," that aficianados of the

cult liked best to foregather.

It was the morning of the Feast of San Antolin of Panticosa, a morning so sweet, and blue and luminous, and many were waiting.

"It's queer the time a man takes to slip on a frilly!" the laundress of the Basilica, Doña Consolacion, observed, through her fansticks, to Tomás the beadle.

"Got up as you get them...."

"It's true, indeed, I've a knack with a rochet!"

"Temperament will out, Doña Consolacion; it cannot be hid."

The laundress beamed.

"Mine's the French."

"It's God will whatever it is."

"It's the French," she lisped, considering the silver rings on her honey-brown hands. Of distinguished presence, with dark matted curls at either ear, she was the apotheosis of flesh triumphant.

But the entry from the vestry of a file of monsignore imposed a transient silence—a silence which was broken only by the murmur of passing mule bells along the street.

Tingaling, tingaling: evocative of grain and harvest the sylvan sound of mule bells came and went.

Doña Consolacion flapped her fan.

There was to be question directly of a Maiden Mass.

With his family all about him, the celebrant, a youth of the People, looking childishly happy in his first broidered cope, had bent, more than once, his good-natured head, to allow some small brothers and sisters to inspect his tonsure.

"Like a little, little star!"

"No. Like a perra gorda."

"No, like a little star," they fluted, while an irrepressible grandmother, moved to tears and laughter, insisted on planting a kiss on the old "Christian" symbol. "He'll be a Pope some day, if he's spared!" she sobbed, transported.

"Not he, the big burly bull." Mother Garcia of the Company of Jesus addressed Doña Consolacion with a mellifluent chuckle.

Holding a bouquet of sunflowers and a basket of eggs she had just looked in from Market.

"Who knows, my dear?" Doña Consolacion returned, fixing her gaze upon an Epitaph on a vault beneath her feet. "'He was a boy and she dazzled him.' Heigh-ho! Heysey-ho...! Yes, as I was saying."

"Pho: I'd like to see him in a Papal tiara."

The Flower Beneath the Foot

The Flower Beneath the Foot Sorrow in Sunlight

Sorrow in Sunlight Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli

Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli